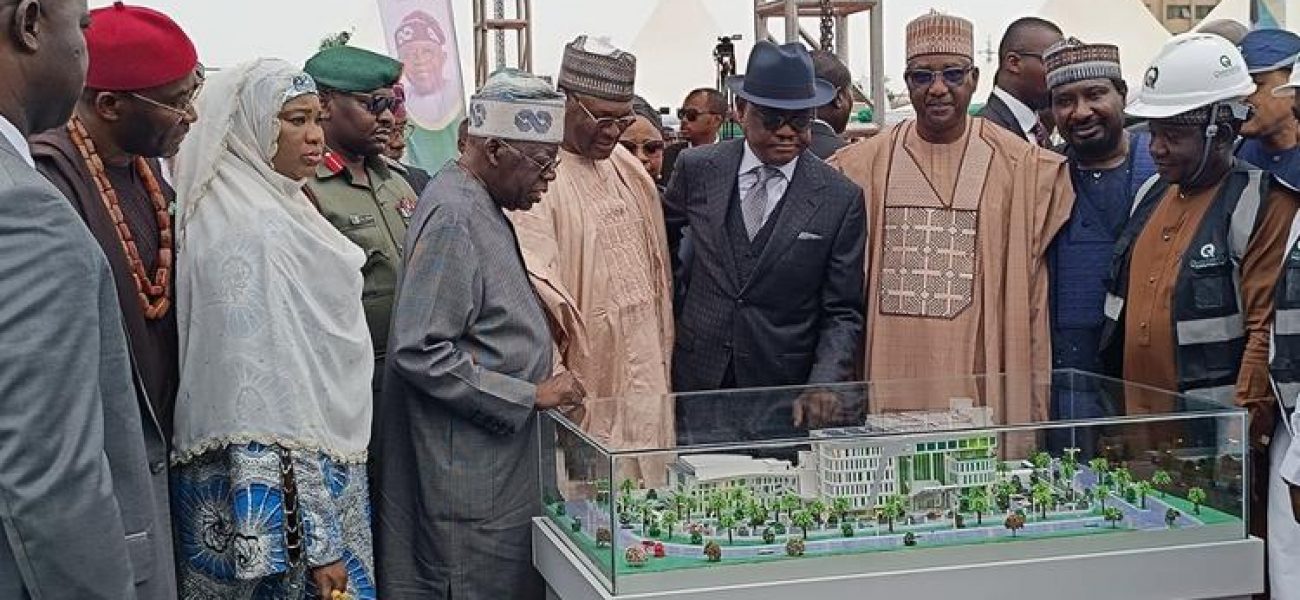

As part of activities marking President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s second year in office, the Federal Capital Territory Administration (FCTA) has flagged off the construction of a new headquarters for the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) in Abuja. While this development has been presented as a routine capital project under the FCTA, it raises legitimate questions about the optics, propriety, and implications for the independence of Nigeria’s electoral body.

The proposed headquarters, to be sited in the Maitama District of Abuja, is reportedly being executed by the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA) under the supervision of the FCT Minister. Though details of the project remain unclear, especially regarding its budgetary allocation and overall cost, estimates suggest it will run into billions of naira. Given the strategic importance of INEC in Nigeria’s democratic process, this initiative has already generated concerns in civic and political circles.

At the heart of the concern is the question: Should the FCTA be the one to build the headquarters of an electoral umpire meant to be independent and neutral?

INEC is constitutionally recognised as an independent body, with a mandate to oversee free, fair, and credible elections in Nigeria. While the FCTA has historically been responsible for building and maintaining key federal institutions within the capital, including the National Assembly and the Presidential Villa, INEC’s unique role in democratic governance sets it apart. It is not just another public institution—it is the very engine room of electoral legitimacy.

Critics argue that allowing a politically appointed minister, especially one with a well-known partisan history, to oversee such a sensitive project could send the wrong signals about institutional autonomy. This is especially troubling in a pre-election context, where perceptions of bias, whether real or imagined, can have far-reaching consequences for public trust in the electoral process.

The FCT Minister’s recent controversies, including the construction of residential quarters for judges, have already attracted scrutiny, with some accusing the administration of using public infrastructure projects to curry institutional goodwill. A similar perception could trail this INEC headquarters project, particularly in the absence of transparency around funding, procurement, and project oversight.

There is also the issue of budgetary clarity. Although the National Assembly has reportedly approved the 2025 FCTA budget, it is yet to be assented to by the President, and no official breakdown has been provided on whether the INEC building is specifically captured in the fiscal plan. In a democracy where accountability in public spending is critical, such opacity undermines confidence in the intentions behind the project.

While defenders of the initiative argue that INEC, as part of the executive structure, can legitimately receive infrastructural support from the government, this argument overlooks the symbolic and functional autonomy required of an electoral commission. Independence is not just a matter of legal status; it is also about perceived distance from political influence.

As Nigeria prepares for another pivotal general election in 2027, the independence of INEC must not only be preserved—it must be seen to be preserved. Any action, no matter how well-intentioned, that risks undermining that perception deserves scrutiny.